Presented at the Society for Applied Anthropology

(TH-160) THURSDAY 5:30-7:20, April 6, 2018

CHAIR: WILSON, Jason (TGH, USF)

Opening Remarks

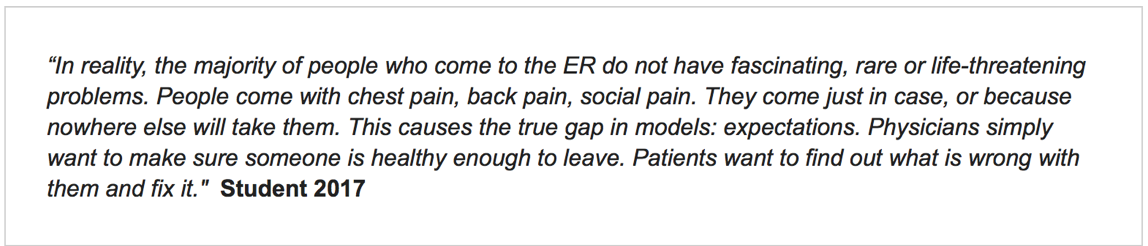

A gap exists between patient and provider expectations during healthcare encounters in the United States. Those gaps are especially prevalent in acute clinical settings such as the emergency department where physicians have a defined agenda to rule out life threatening disease within a small amount of time usually with a patient they do not know from previous visits. Sometimes the underlying reason for the ER visit is emergent and sometime it is not, sometimes the underlying reason is medical and sometimes it is not.

Arthur Klieinman framed the patient-physician gap over 30 years ago as a difference in explanatory models of disease and illness. Medical anthropologists have focused on the tension between biomedical and lay person models of health. However, the patient experience, as measured by healthcare surveys of satisfaction, has not improved significantly and may be even worse in a setting of overcrowded department, confusing healthcare insurance issues, and disjointed attempts at continuity.

Attempts to measure the existing gap between an ideal patient experience and the current state were formalized by Irwin Press in the 1980s with the now ubiquitous utilization of the Press-Ganey Survey. However, just because a phenomenon is measured does not mean that the problem is resolved.

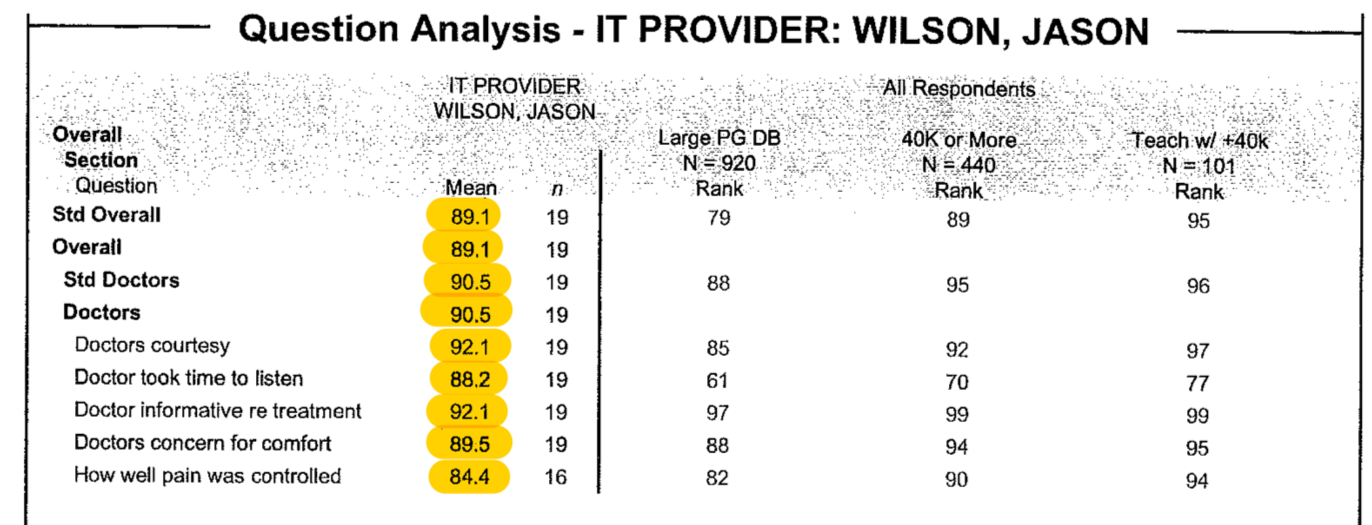

Hospitals spend millions to improve the patient experience, or at least to improve scores on patient satisfaction surveys. Those scores are now tied to reimbursement and the proportion of reimbursement related to those scores will only increase for providers and facilities moving forward.

What do hospitals get for all of this spending on patient satisfaction? Essentially everyone achieves mediocrity. The spread around the mean of these scores is incredibly tight. Moving from 83% to 85% might move you from the 50th percentile to the 90th percentile. The first large spend on patient experience by healthcare facilities is to ensure 50th percentile – drop below that and you risk a loss of federal reimbursement. The goal, however, is to ultimately move above average since that is where the rewards for higher patient satisfactions scores exist. Thus, hospitals spend incredible amounts of money to improve a few percentage points but, as the score gets higher the ability to increase the score by another percent also becomes exponentially more expensive.

Four years ago, a medical anthropologist and an emergency medicine physician decided to approach this issue together by repositioning the role of medical anthropology education in the premedical school curriculum as well as to position medical anthropologists as the obvious human resource for a healthcare organization patient experience department. As an ER doc who also went through the same training as our current students are just embarking upon, it was important to me to provide access to shadowing and research opportunities but with enhanced student engagement.

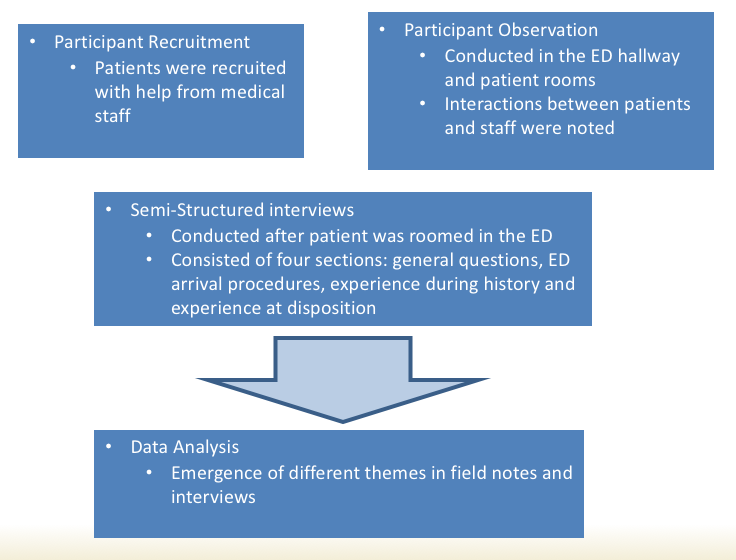

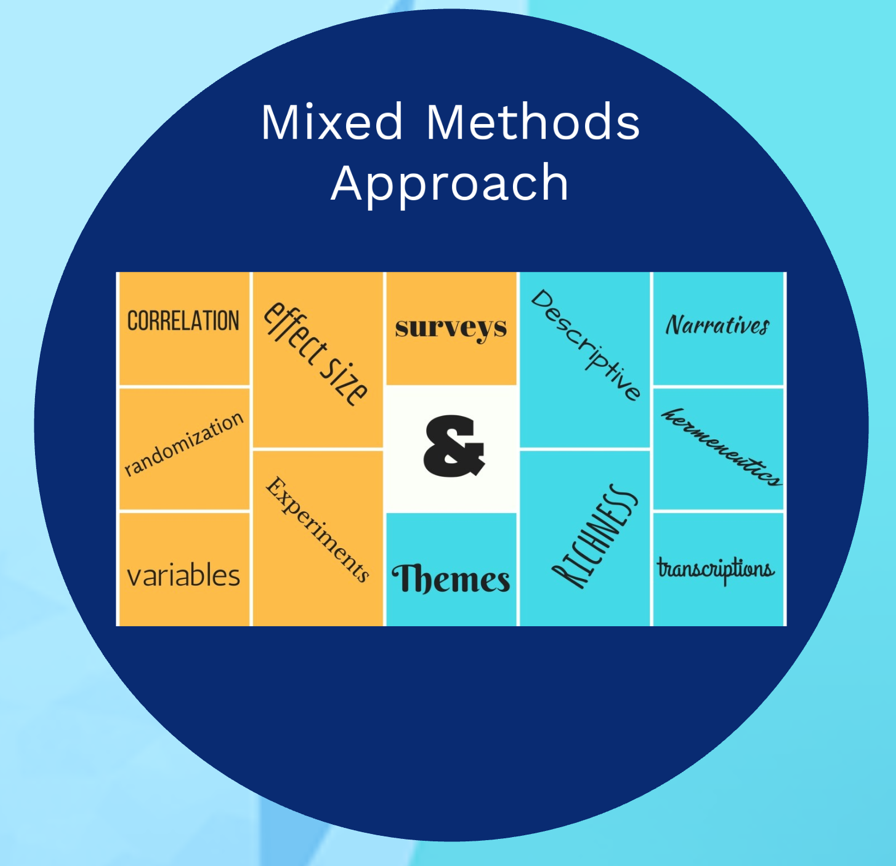

The papers you will hear this afternoon arose from this ongoing work. In the spring of 2015, we designed and co-taught our first iteration of an undergraduate course for pre-medical students, ANT4970 Patient-Physician Interaction. Now on our third rendition, each semester students first spend time shadowing patients and developing a patientcentric lens early in medical training. Student also learn the importance of utilizing mixed-method approaches such as participant observation, semi-structured interviews and quantitative analysis of data, to address questions focused on improving the overall patient experience. This course has had a tremendous impact on undergraduate students who often cite the class as a life changing experience.

The papers you will hear this afternoon arose from this ongoing work. In the spring of 2015, we designed and co-taught our first iteration of an undergraduate course for pre-medical students, ANT4970 Patient-Physician Interaction. Now on our third rendition, each semester students first spend time shadowing patients and developing a patientcentric lens early in medical training. Student also learn the importance of utilizing mixed-method approaches such as participant observation, semi-structured interviews and quantitative analysis of data, to address questions focused on improving the overall patient experience. This course has had a tremendous impact on undergraduate students who often cite the class as a life changing experience.

Many of those students are now in medical school and Roberta Baer, Seiichi Villalona and I are following them and examining the sustainability of their early patientcentric training as they move through their training. Many students stay with us to complete undergraduate honors theses and we have now expanded our work in the ED to also include anthropology graduate students conducting dissertation research. This approach allows us to position graduate students as experts in patient experience within our institution and also to provide early, sustainable, training in patientcentric care that will, hopefully, be sustained as these trainees become physicians. Ideally, the course can be scaled up to other institutions, positioning med anthro training as a crtical aspect of improving patient experience.

Many of those students are now in medical school and Roberta Baer, Seiichi Villalona and I are following them and examining the sustainability of their early patientcentric training as they move through their training. Many students stay with us to complete undergraduate honors theses and we have now expanded our work in the ED to also include anthropology graduate students conducting dissertation research. This approach allows us to position graduate students as experts in patient experience within our institution and also to provide early, sustainable, training in patientcentric care that will, hopefully, be sustained as these trainees become physicians. Ideally, the course can be scaled up to other institutions, positioning med anthro training as a crtical aspect of improving patient experience.

The ability to move a patient satisfaction score from the 50th percentile to the 90th percentile is expensive and difficult. Mainstream medical approaches focus on reinforcing techniques that improve the perception of time spent with the provider during an acute clinical encounter as well as enhanced customer service approaches adopted from customer service friendly business, such as luxury hotel chains and well known amusement parks.

However, the premise of the work you will hear today suggests that those experience improvements may only be possible if specific special populations are better understood and addressed in the ED. The variation in patient visits and patient satisfaction scores is not described in the current Press-Ganey database and might not be well captured in quantitative analysis of large datasets. That is why these papers are critical to advancing our understanding of the patient experience in the ED.

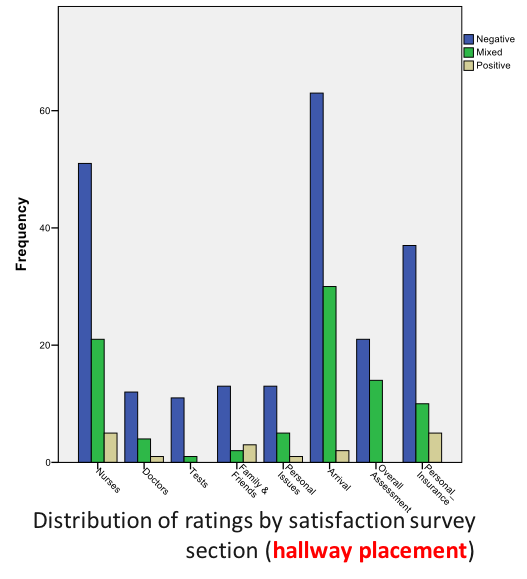

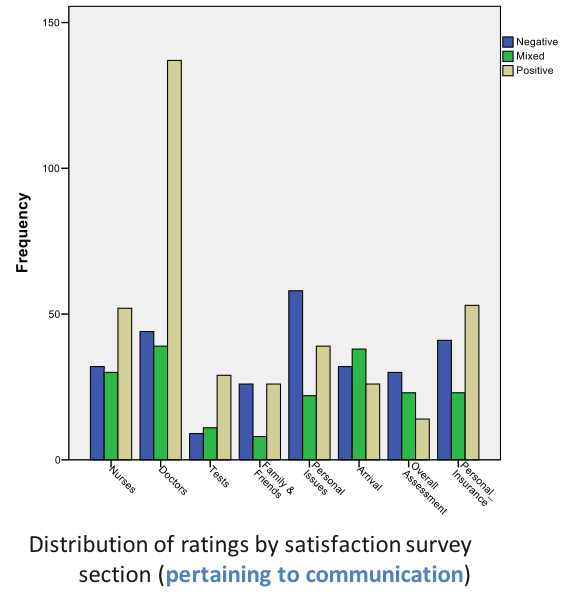

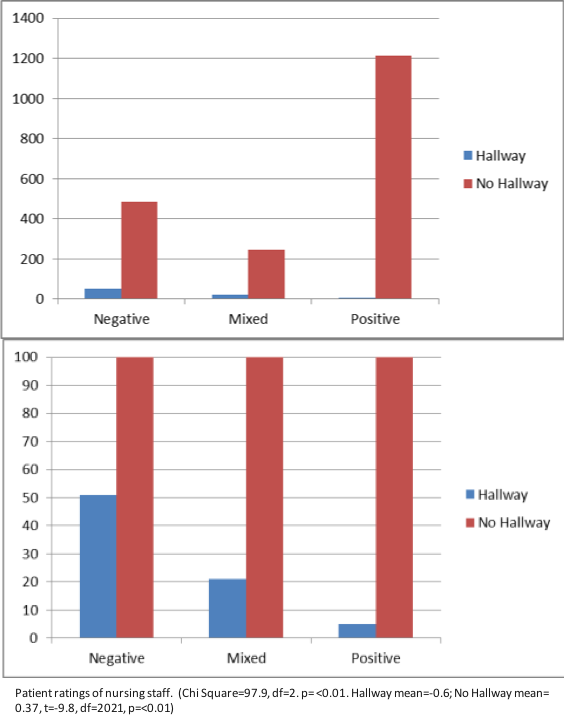

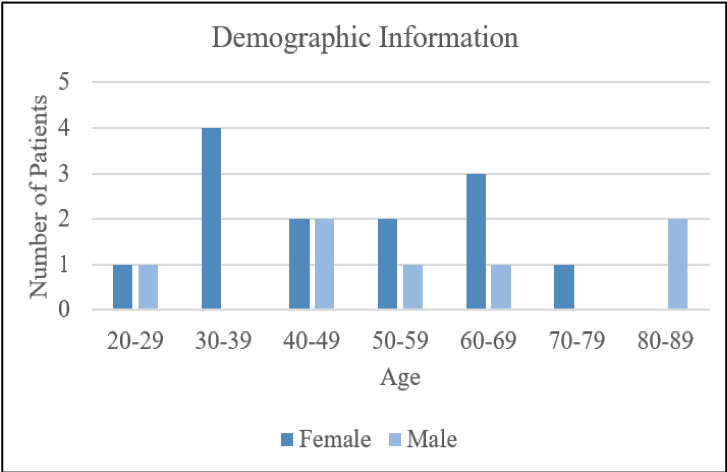

First, you will hear from Seiichi Villalona. Seiichi is a graduate student receiving an MA this semester and moving on to the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Jersey this fall. Seiichi’s work focused on the relationship between placement of patients in less-optimal areas of the ED, such as hallways, and how those circumstances effect the overall experience. Seiichi’s thesis work is on the use of medical interpreters which he conducted with both one of our ED residents as well as another presented today, Mery Yanez Yuncosa who completed her undergraduate honors thesis examining Spanish patients who receive variable translation services in the ED.

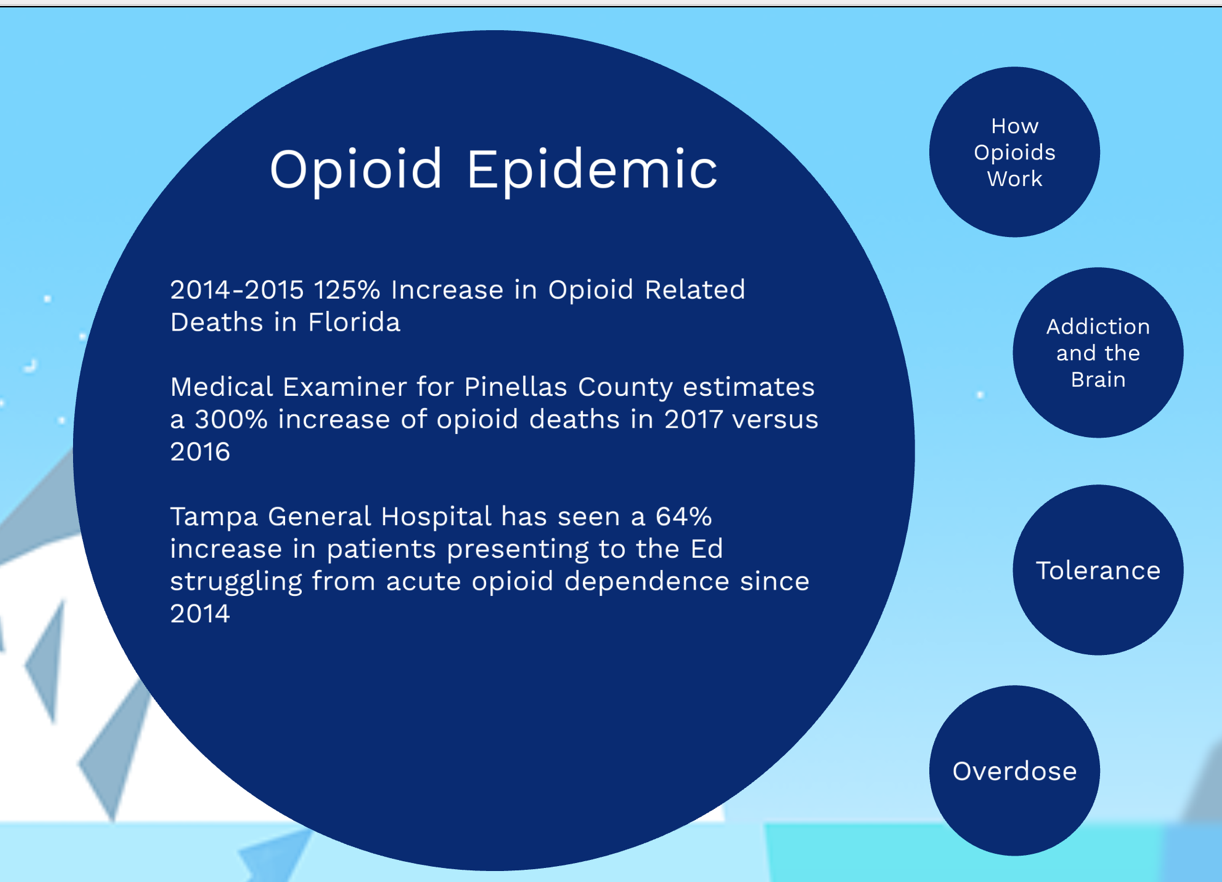

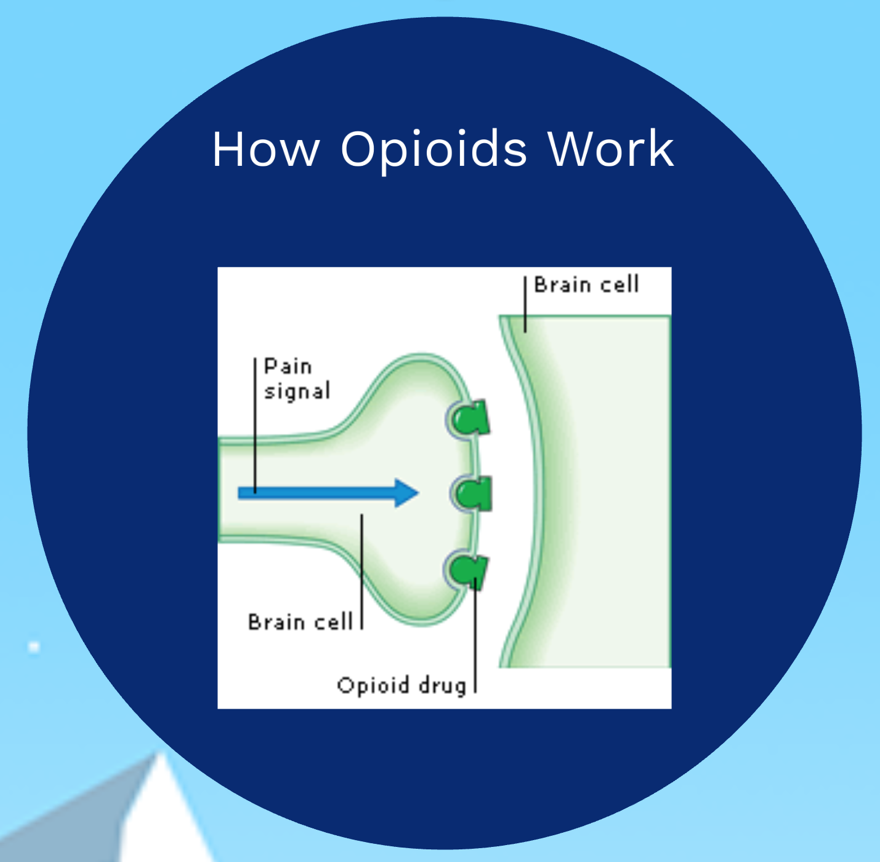

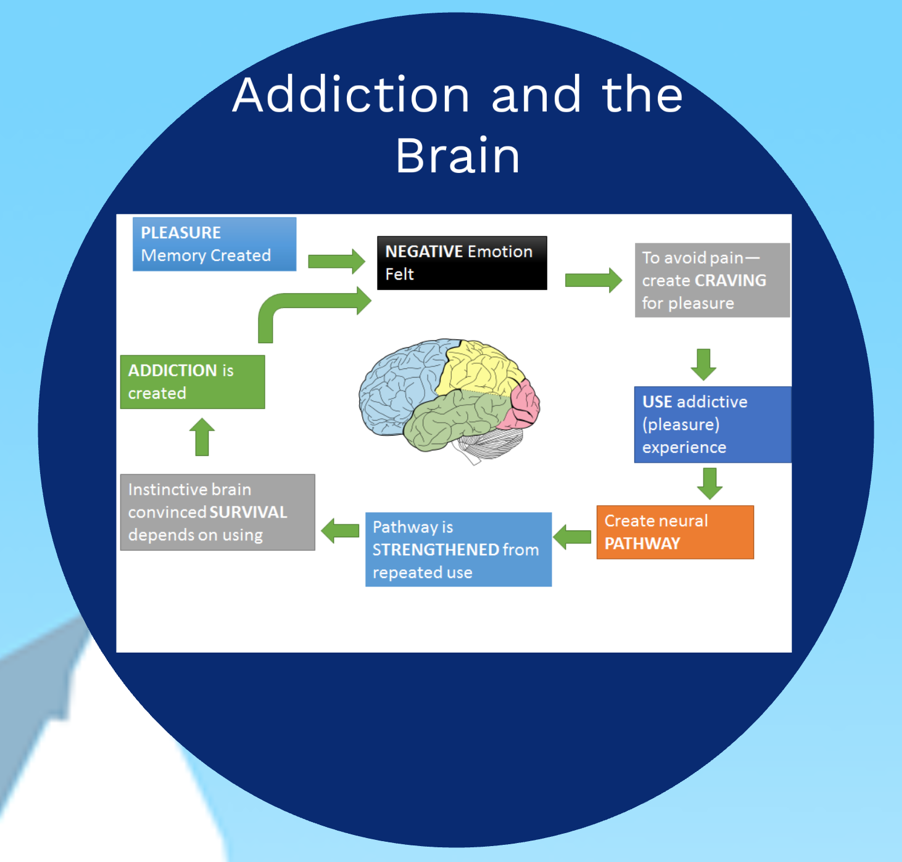

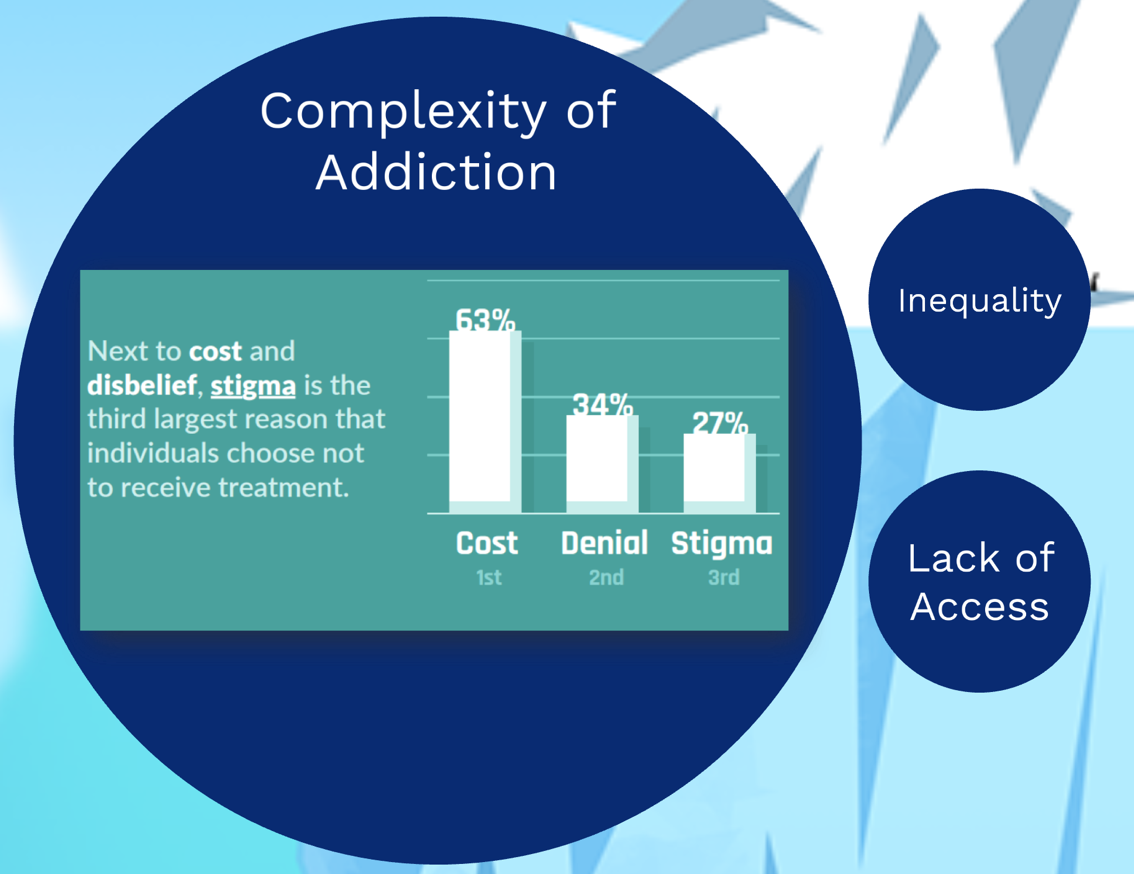

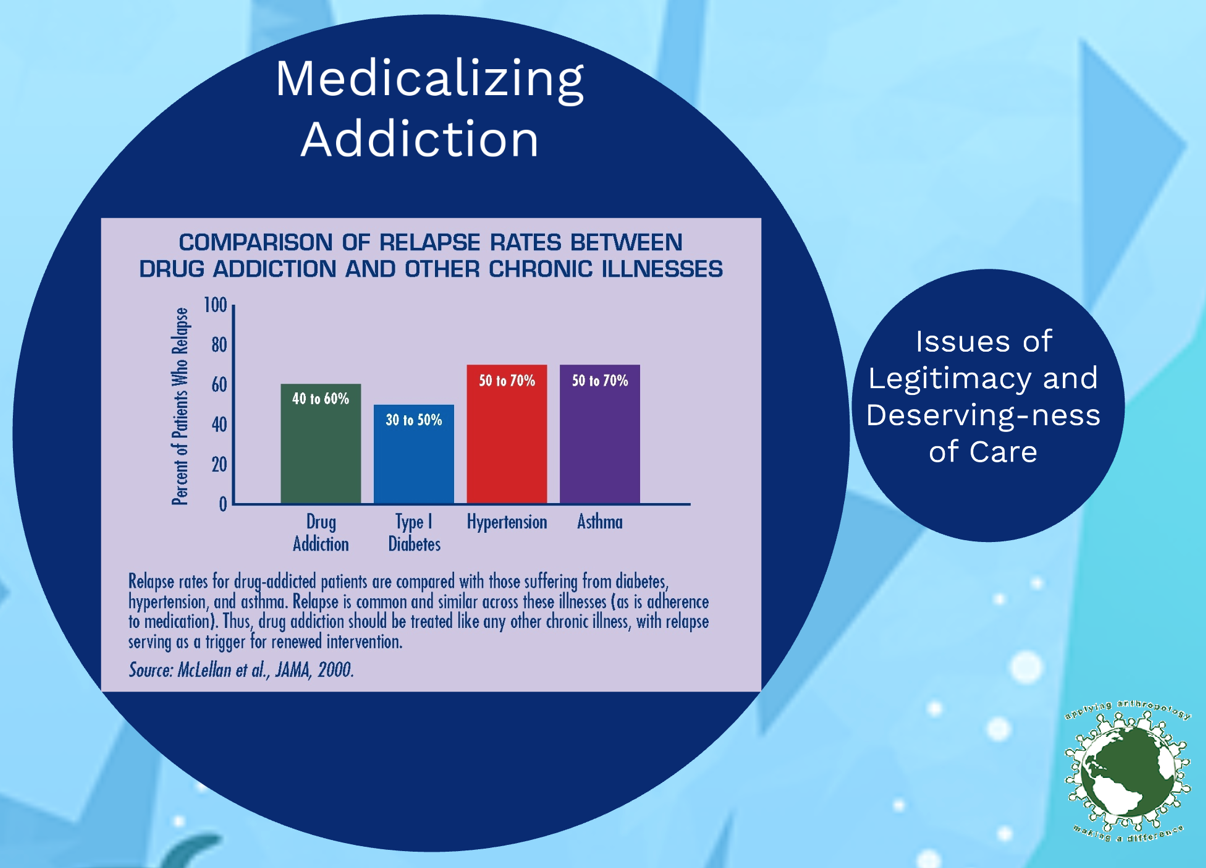

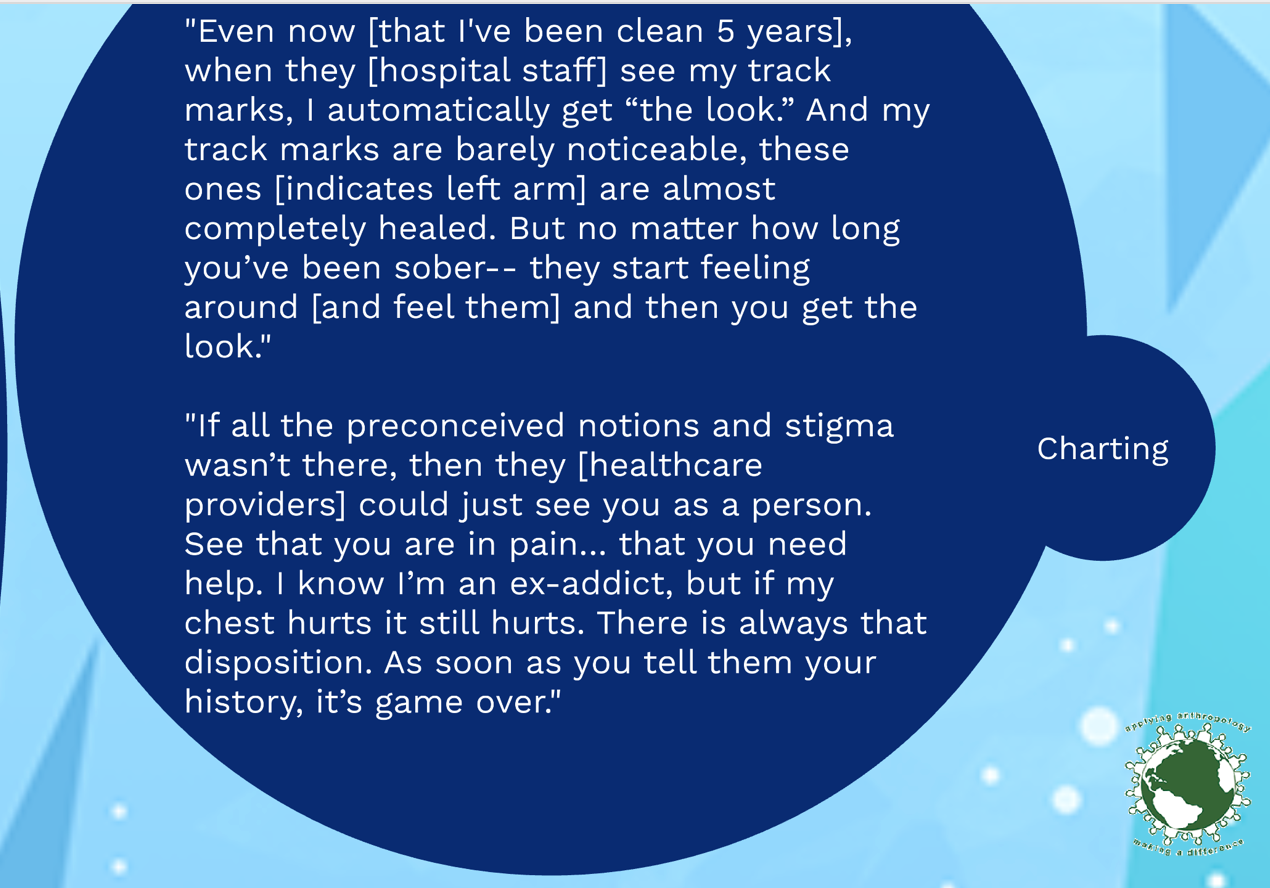

We will also here from another undergraduate student, Killian Kelly, who is planning to eventually move on to graduate school in anthropology and worked with us to develop a patientcentric generated expectations leaflet. In addition, we will hear from Carlos Osorno Cruz who completed his undergraduate degree in anthropology and stayed on in the Emergency Department to continue his work as a research assistant, focusing on ways to improve the care of patients with sickle cell disease patients in the ED. We will also hear from a PhD Student, Heather Henderson, who has recently completed her master degree work on the stigma of opioid addiction. Heather’s work focuses on the medicalization of opioid abuse and how we can work to decrease the marginalization of this population in the ED.

Each presenter will take up to 15 minutes and we will hold questions to the end. After the last presentation, Roberta Baer, the co-designer of this course and these efforts will join us and we will conduct a 15-20 minute discussion and Q&A.

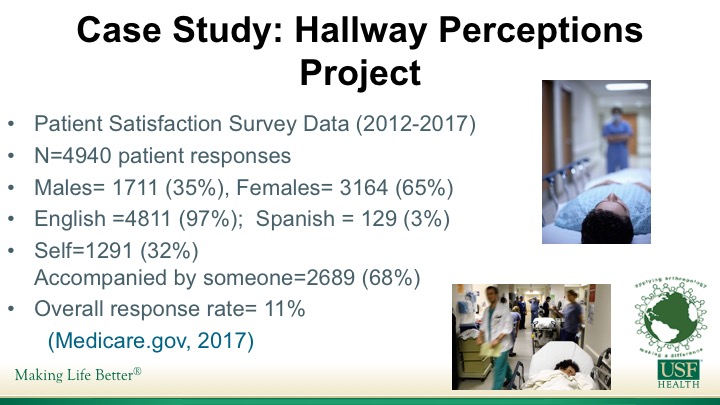

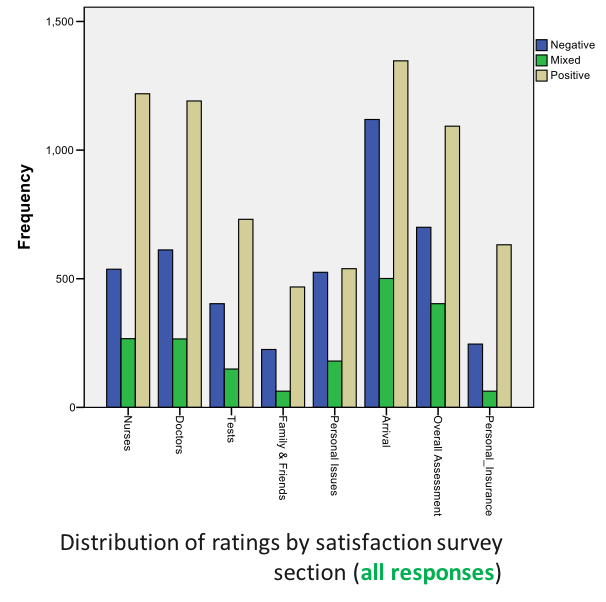

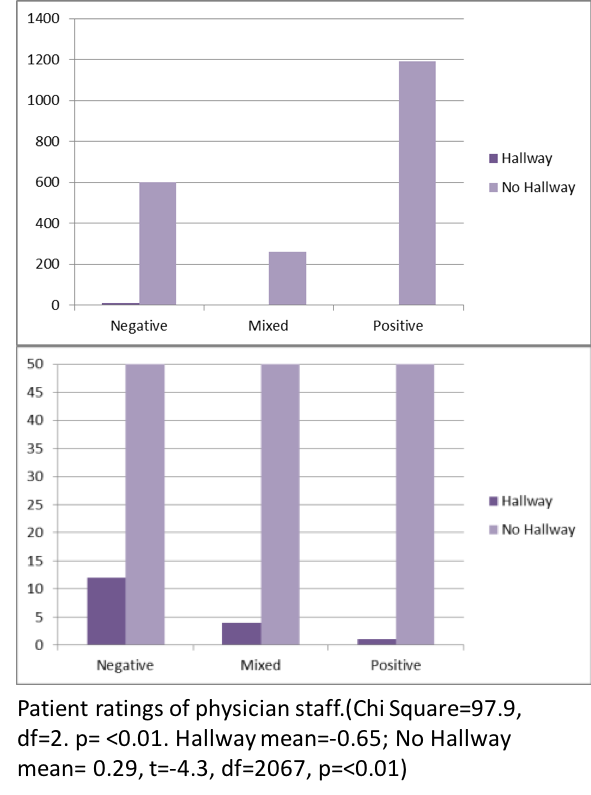

VILLALONA, Seiichi (USF) and WILSON, Jason (TGH, USF) Patient Experience and Patient Satisfaction: Anthropologically Examining the Impact of Hallway Placement on Perceptions of Care

VILLALONA, Seiichi (USF) and WILSON, Jason (TGH, USF) Patient Experience and Patient Satisfaction: Anthropologically Examining the Impact of Hallway Placement on Perceptions of Care

“I was in the hallway the entire time that I was being treated. I do understand that the ER was very busy and I am appreciative that I was seen and treated but I felt invisible most of the time that I was being treated even though I was visible to everyone that walked past. I did not even have a screen up around me and at one point the screen beside my gurney was taken to use for someone else. I do not think I would have minded so much if I would have been asked if I wanted it to be used for me first.” -58 year old female

“Nurses were sitting in station talking about personal matters. I was left in the hallway feeling uncomfortable with other visitors passing by and not being informed of anything.” -57 year old female

YANEZ, Mery and VILLALONA, Seiichi (USF), WILSON, Jason (TGH, USF)

YANEZ, Mery and VILLALONA, Seiichi (USF), WILSON, Jason (TGH, USF)

HENDERSON, Heather (USF) and WILSON, Jason (TGH, USF) Evolving Epidemiology: Perceptions of Stigma and Access to Care in Acute Opioid Crisis

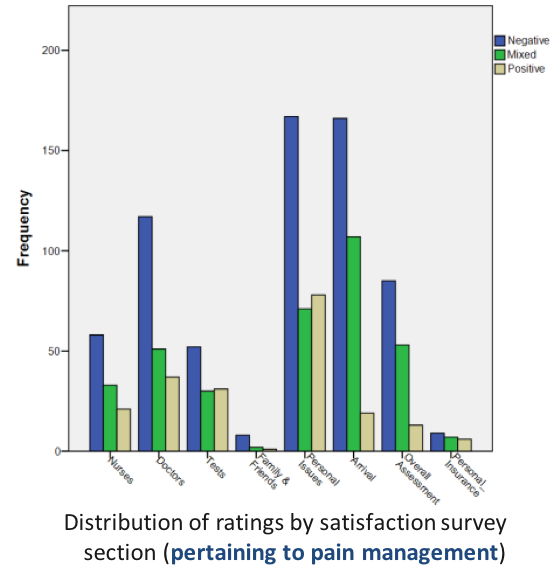

OSORNO CRUZ, Carlos (TGH) and WILSON, Jason (TGH, USF) Understanding the Sickle-Cell Patient Experience and New Approaches to Pain Management

- Patients have unmet expectations

- lack of high quality evidence based approaches to management

- the subjective nature of VOC-related pain and the likelihood of opioid dependence.

- During a 3 year period from Nov 1, 2014 – Oct 31, 2017, there were 2,742 SCD encounters related to pain crisis

- 280 unique patients.

- On average, there are 2.17 SCD encounters daily

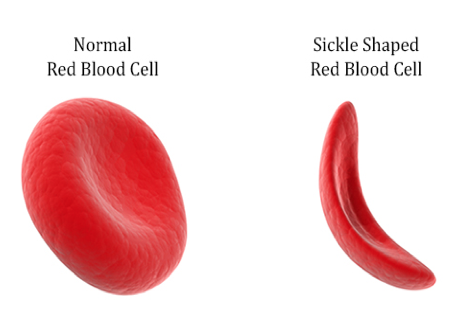

- a genetic, chronic blood disorder

- effects 100,000 people in the United States

- causes multiple medical problems including anemia, immune-dysfunction, stroke

- frequent episodes of acute pain (sickling crises or vaso-occlusive crises (VOC))

- 1 out of every 365 Black or African-American births

- 1 out of every 16,300 Hispanic-American births

- About 1 in 13 Black or African-American babies is born with sickle cell trait

What have we done to improve patient care?

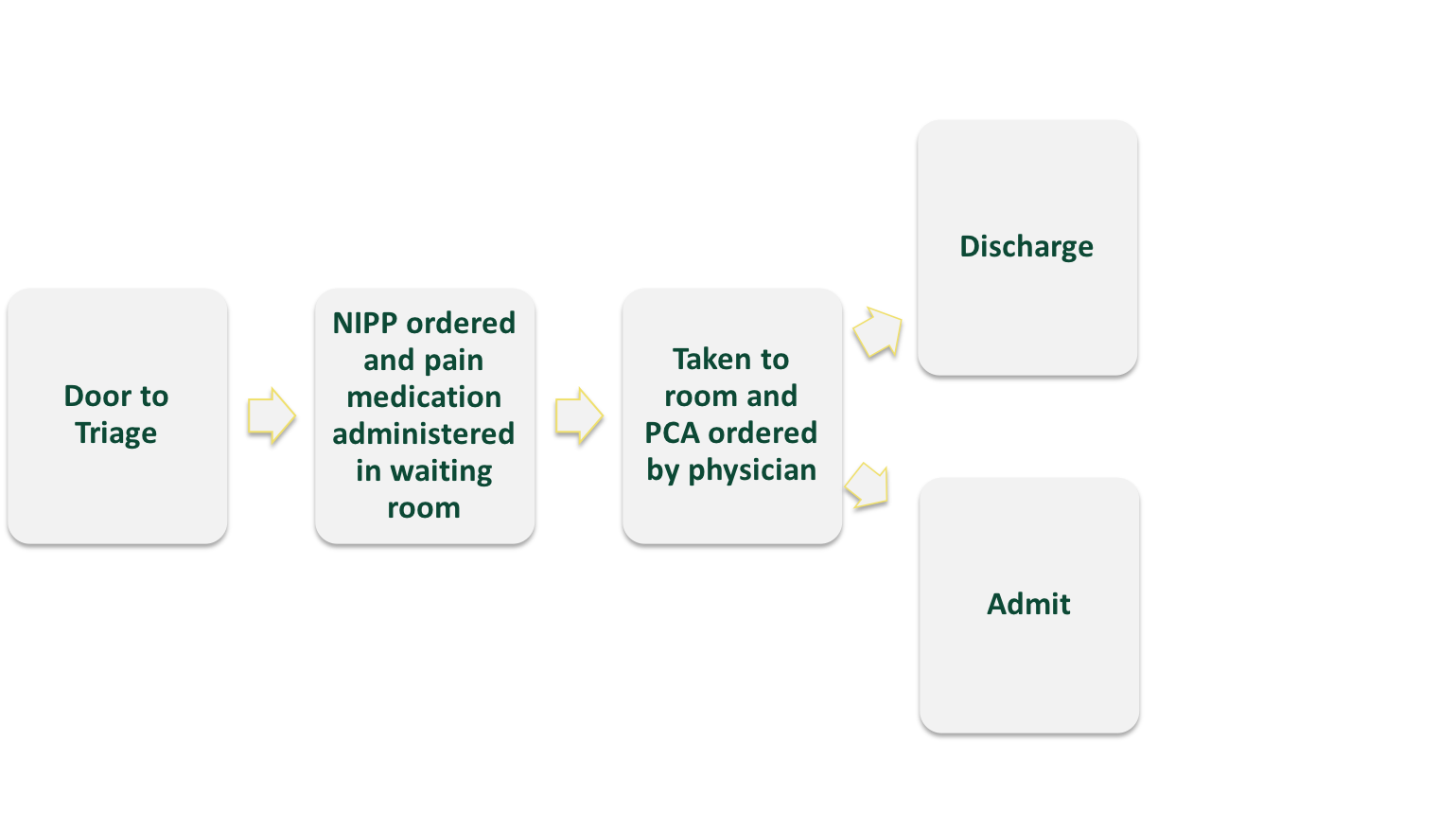

- worked to create an environment of clear expectations for providers and patients with SCD that present to the ED

- developed a patient controlled analgesia strategy to help meet expectations for pain management during ED visits

- currently working with a newly formed national ED SCD quality group to achieve a best practice approach

- Patients and healthcare providers perspectives on current care at TGH ED were collected through interviews while in the ED and infusion clinics.

- Unique patient visits decreased from 2.17 encounters per day to 1.33 encounters per day

- Each patient that encountered our ED during the study period also visited less often, decreasing their visit rate by 38%

- the admission rate declined from 69% in 2015 to 59% in 2017

- ED LOS did not increase more than the entire ED LOS increased during the same time period for all patients (18%)

- During the period reviewed, the rate of patients that left without being seen and against medical advice decreased by 33%

- The hospital LOS for admitted patients with SCD VOC did not change significantly during this period

- patients that received a PCA had a longer time period until pain medication administration (30 min w/o & 47 min w/)

- The overall rate of PCA use increased from 8% to 65% during this period.

Patient Perspectives

“Having the PCA makes our treatment the same”

“We know our bodies better than they do”

“Call my doctor immediately not 3 hours later when you realize nothing is working”

“We aren’t taken serious”

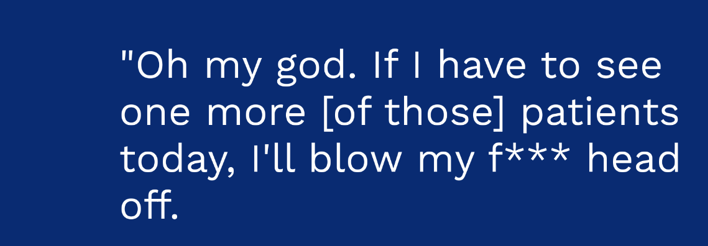

Healthcare provider Perspectives

“they’re just drug seeking”

“they’re taking advantage of us”

“if we give them what they want they won’t stop coming”.

- results support utilization of a PCA in patients with SCD VOC and suggest a potentially positive impact on patient flow

- continued buy in from both healthcare providers and SCD patients is critical to ensure best practice

- During triage patients like to be asked “what works for you?” followed with a loading dose through a NIPP order

- Patients preferred to be discharged rather than admitted into “prison” matching the ED goal.

Unresolved Issues

- RN’s not ordering pain meds with NIPP

- PCA is not being used by all physicians

- Healthcare providers misunderstanding sickle cell patients

- Time to PCA set-up

Future Directions

1.Use NIPP approved for SCD Pain Crisis Including Pain Medication (essentially 0% use previous to 2018)

2.Decrease Door to Drug Time. Goal of 30 minutes to pain med (NIPP Utilization while awaiting PCA)

3.Increase PCA use (don’t expect 100% given NIPP use may decrease need for further IV meds)

4.Decrease SCD Pt Admission rate to overall ED admission rate (40%)

5.Decrease ED LOS D/C SCD Pts to 80% of pts D/C in 240 minutes

6.Decrease ED LOS Admit SCD Pts to 80% of pts in 420 minutes

Upcoming Interventions

1.Continue work with hospital VP on educational Video – multi-specialty collaboration for RNs to increase NIPP medication order utilization and acknowledgment of SCD patients

2.TGH Infusion Center and TGH Output Med working with ED to facilitate pathways

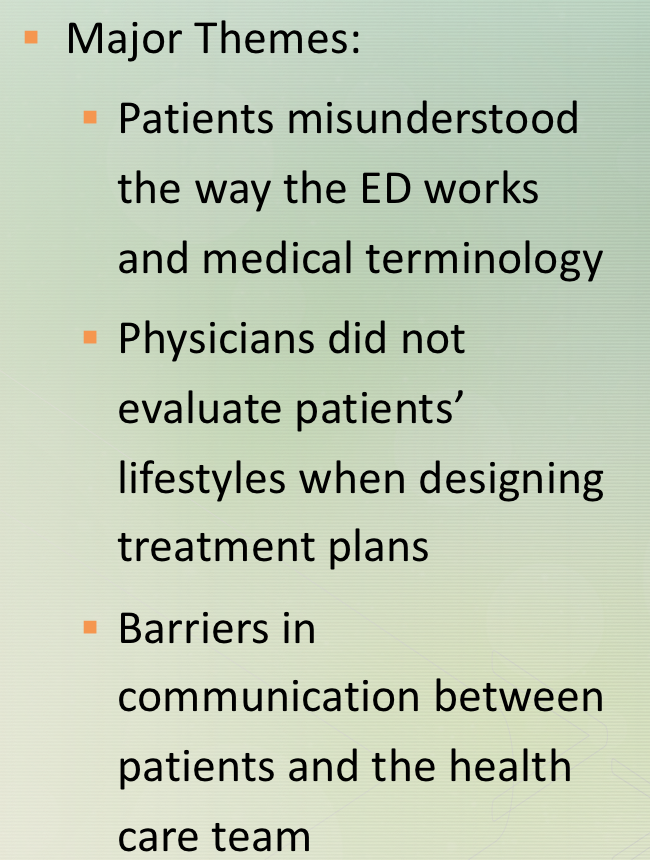

KELLY, Kilian and BAER, Roberta (USF), WILSON, Jason (TGH, USF) The Patient Perspective: Applying Medical Anthropology to the Patient Experience in the Emergency Department

Implementing a program like this leaflet would allow patients to enter the ED with a better understanding of what is going on around them.

Closing Remarks From Session Chair Jason W. Wilson, MD, MA, FACEP

Discussion and Q&A Led by Course Co-Designer Roberta Baer, PhD

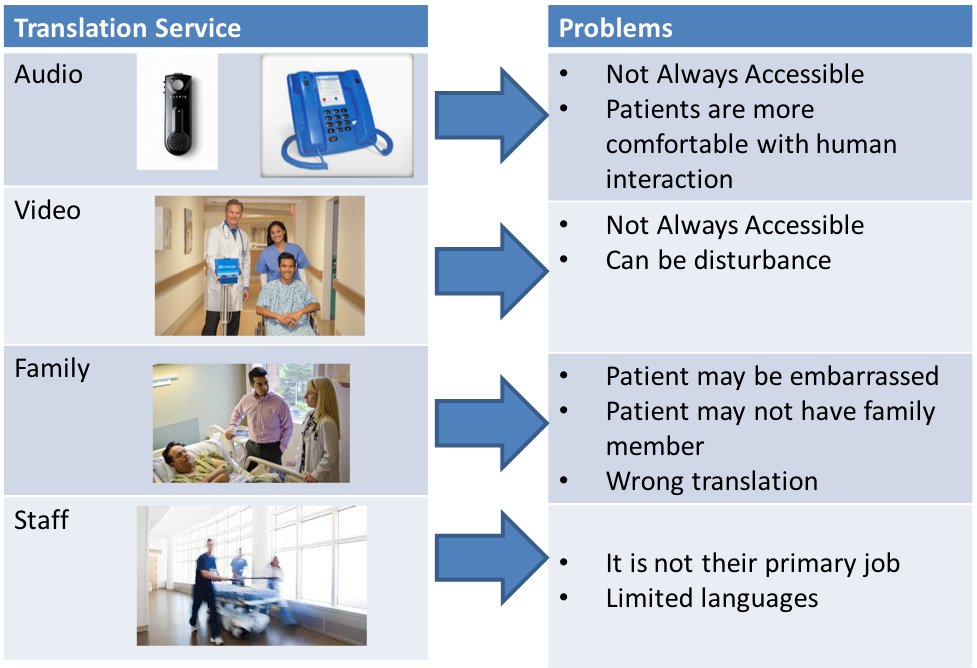

I have been guilty of under communicating in the ED – we are busy and we want to move on to the next patient. However, graduate student Seiichi Villalona and PGY-3 Christian Jeanot, MD, along with undergraduate Mery Yunez Yucosa have all been working to demonstrate the value of professional video translation services in the ED.

I have been guilty of under communicating in the ED – we are busy and we want to move on to the next patient. However, graduate student Seiichi Villalona and PGY-3 Christian Jeanot, MD, along with undergraduate Mery Yunez Yucosa have all been working to demonstrate the value of professional video translation services in the ED.